Introduction:

In 1983, four architects in Kansas City decided to build a practice exclusively focused on sports arenas: HOK Sport, now called Populous. Dennis Wellner was one of those four, and football stadiums became his niche. Since that time, perhaps no other person has had a hand in more football stadium designs.

Joe Robbie Stadium in Miami became their first major project to host an NFL game, in 1987. The second was what we now call the Edward Jones Dome, built to lure the Los Angeles Rams to St Louis in 1995. Barely fifteen years later, the dome has become the 19th-oldest stadium in the league, and questions of its ability to support the Rams long term have arisen.

I was lucky enough to spend some time talking with Wellner about the unique challenges of NFL stadium design, the history of the Edward Jones Dome, and the possibilities facing the Rams in the coming years. This article is the first of two that span that interview. Because there is no active project between the Rams and Populous, we couldn’t go into specifics about the Rams’ next steps. But I was able to tap into his wealth of experience in the area, and give you an idea of the factors that Stan Kroenke and company will be considering.

History of ballpark design

Fenway Park’s dimensions are naturally constrained by its sliver of a footprint, turning the foreshortened left field wall into the infamous “Green Monster.”

Fenway Park’s dimensions are naturally constrained by its sliver of a footprint, turning the foreshortened left field wall into the infamous “Green Monster.”The urban baseball park – a carefully sheltered patch of green playing field carved into the cityscape – became the first iconic example of sports architecture. They were truly products of their urban environment (like Wrigley Field in Chicago), and the flexible rules regarding dimensions allowed them to integrate into the urban fabric in creative ways (like the Green Monster in Boston). By contrast, the original football stadiums with their fixed dimensions were little more than ossified bleachers surrounding an Olympic-scale track and field.

But ballpark design got swept up in a popular desire for “convertible” stadiums, cookie-cutter concrete bowls like the old Busch Stadium that were built to house football and baseball, truly accommodating neither. These instant relics sprouted up all over the country in the 60s and 70s in St Louis and other cities like Atlanta, Queens, and Philadelphia. The only love given them by fans was that earned by the teams within; and in the case of the ill-fated football Cardinals, that was little indeed.

Populous’ Oriole Park in Baltimore (opening in 1993) was the first of the new dedicated baseball parks to bring back the tradition of integrating the game with its city, its surrounding architecture, and its culture. Oriole Park was widely acclaimed for delivering a “feel” for baseball that was both unique and timeless, and has been followed by other award-winning designs including Progressive Field in Cleveland (fondly called “the Jake”), AT&T Park in San Francisco, and Petco Park in San Diego. The same philosophy of integrating the local skyline and iconography led to the beautiful sightlines of the new Busch Stadium in St Louis.

Differences between baseball and football.

Where baseball stadium designs often look toward “tradition,” modern football stadium design can become almost sculptural, like Heinz Field in Pittsburgh.

In terms of their location, Wellner rarely has been given his choice of site; many complicated factors are involved in finding the right property, whether in an urban downtown setting or scattered in a barely settled suburban plain. He does have a personal preference, though:

“Baseball parks should always be downtown. But for football, they can work either way.”

Whether the setting is urban or suburban, Wellner continues, “As a designer there are ‘correct’ approaches; it’s more about using a site that is appropriate for the myriad issues surrounding the team, the city and the deal.”

Because they integrate into the densely packed city grid, downtown stadiums can’t often be seen from afar, and they are literally surrounded by the city’s heart and history. For these reasons, Wellner states, “Downtown stadiums have to be much more conscious of the surrounding architecture.”

The St Louis red clay brick facade of Busch III would fit easily among the brownstones of Lafayette Square, the French Colonial architecture of Soulard, or the original brick and terra cotta skyscrapers (some of the first in the country) of downtown St Louis. Petco Park in San Diego takes the concept to a whole new level, incorporating the historic Western Metal Supply building into the field of play.

Suburban stadiums, by contrast, are often surrounded by empty parking lots, and can be seen and appreciated from quite a distance. “As a result,” says Wellner, “their exterior design can be much more ‘sculptural.’ ” Examples of this range from the graceful double arches of Qwest Field in Seattle to the modern exterior expression of Paul Brown Stadium in Cincinnati; from the daringly deconstructed silhouette of Heinz Field in Pittsburgh to the amusement park feel of Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, complete with pirate ship.

Regardless of location or of the shape of the footprint, Wellner says there are two primary design concerns for the architect: “Make the design work for the sport, and express yourself artistically. But the context, the influence of the region, and the community it will live in all have to be considered.”

1993-2010: The NFL Stadium Boom

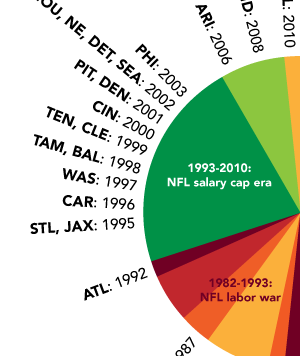

The art of stadium building has now become a well-practiced craft. As becomes evident when looking at the last 30 years of NFL labor bargaining, the salary cap era that started in 1993 has led directly to a stadium construction boom.

Since the Jones Dome opened in 1995, nineteen more NFL stadiums have dotted the countryside — twelve of which were designed by Populous. And Commissioner Goodell isn’t ready to stop there.

“We need new stadiums in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Oakland and San Diego.”

— NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell.

In his recent open letter from the NFL, Goodell holds up this need as a primary reason for the league’s desire to take another billion dollars of annual league revenue off the top and spread it among the owners.

Size wise, the footprint of football stadiums has increased over this time: where 1.6 million square feet of space sufficed in the past, now closer to 2 million is the norm, and your “super stadiums” like Jerry Jones’ texas-sized Cowboys Stadium can take up 3 million square feet of space. Despite their bulked-up size, stadiums are still generally built to support a capacity of around 65,000 fans, which is a sweet spot of revenue-generating seats and enough of a pinch on capacity to enable frequent sellouts. However, those stadiums that are built in sunny, Super Bowl-friendly spots — think Houston, New Orleans, Tampa, Miami — need to be able to expand capacity easily for the big event by 10 to 20,000 seats. (The inability to pull this off effectively in Dallas currently has the league facing lawsuits from 800 extremely angry fans.)

As the Rams’ lease in the Edward Jones Dome is set to expire in 2015, the open question here is whether St. Louis will appear on Goodell’s stadium wish list in the next five years.

This article is part one of our interview with Dennis Wellner, senior architect at Populous. Part two focuses on the “life cycle” of modern NFL stadiums, and whether after 20 years, the Jones Dome should be considered “old.”