The key word for architecture of this generation is “sustainability.” This has a lot of meanings, from limiting the environmental impact of construction to the long-term health and financial viability of the stadium itself.

This will be a key consideration for Kroenke and the Rams: the Jones Dome will be twenty years old in 2015. Is that “old”? As has been well-reported by this point, the Rams have an opt-out clause in their stadium lease in 2015 if the Dome isn’t one of the top 25% of stadiums in the league. Certainly that isn’t the case today. Can it have a “sustained” life beyond that point?

Part two of our interview with Dennis Wellner, senior architect at Populous (formerly HOK Sport, designers of the Edward Jones Dome), looks at the many facets of sustainability, and what that means to the life cycle of the modern NFL stadium.

Environmental Sustainability

Lincoln Financial Field in Philadephia, soon to be replete with wind turbines. (As envisioned by SolarBlue.)

Lincoln Financial Field in Philadephia, soon to be replete with wind turbines. (As envisioned by SolarBlue.)“The goal of sustainable construction is to have as limited an impact on the environment as possible,” says Wellner.

Regulations for disposal of material waste, which have tightened dramatically in the last thirty years, are only the beginning. “Old concrete from demolished buildings can be ground up and remixed into the foundations of new stadiums,” he explains. “Materials can be locally sourced to limit transportation costs. Wood products, if used in the design, can be sourced from fast-growing and easily-farmed trees.” In many other cases, it is possible to substitute newer non-harmful materials for older messier ones.

And the goal of environmental sustainability doesn’t stop when the construction vehicles roll away. The design of the stadium’s systems — electrical, water, sewer — can all be optimized, sometimes even after the fact. The Philadelphia Eagles just committed $30 million towards installing alternative energy sources like solar panels and wind turbines, essentially allowing the stadium to help power itself.

Financial Sustainability

The Alamodome in San Antonio, which provided the template for the Jones Dome, has hosted the NFL, college football, the NBA, the NCAA Final Four, and multiple concerts and events.

Because a stadium occupies such a large amount of commercial property, it is imperative for the long-term health of the facility that it be able to generate enough revenue to consistently staff and operate the building itself, and return a reasonable profit back to the team who owns it. This is a critical problem in the NFL, whose ten-game home schedule (counting the preseason) leaves 355 days of unoccupied time.

“Even though an ideal stadium would be designed solely for the sport of football, the building design has to be flexible enough to attract and support other kinds of events. Concerts, conventions, special sporting events like the Final Four and so on.”

The Dome, then known as the Trans World Dome, was Populous’ first multi-purpose NFL facility to include a convention center.

“We were very proud of the Dome,” says Wellner. “It included everything we knew to be important to the NFL at that time.”

The design of the home of the Rams was influenced strongly by Populous’ work on the Alamodome in San Antonio, an inexpensively built multi-purpose facility that could house football, basketball, hockey, concerts and conventions.

This multi-sport and multi-function flexibility can be a blessing, allowing for great financial sustainability, but it isn’t always ideal. The Spurs, as primary tenants of the Alamodome, heard constant complaints about poor sightlines, and an incomplete array of luxury boxes held down revenue possibilities. After winning one championship there, the Spurs opened a basketball-dedicated venue in 2002, and have won three more since, becoming one of the most successful basketball franchises in the country — an impressive feat in a market deemed too tiny to support any other pro teams.

Meanwhile, the Alamodome continues to operate successfully, even after the loss of its biggest tenant. This is good new for those that hope that even if the Rams seek new digs, the Edward Jones Dome could continue to stand on its own as a key part of downtown. However, one need look only one block south to the empty shell of the St Louis Centre — whose partial demolition was widely celebrated, even by preservationists — to engender doubt.

A key component to keeping a team in the house you’ve built is the ability to maximize revenue. Stadium planners have to be creative in the way they design the fan experience, justifying high ticket prices. “Premium seat products have evolved. The basic terminology of generating revenue from a stadium hasn’t changed,” Wellner says.

There is little difference between the basic concept of a luxury box now and a box seat in an Italian opera house. “However, the ideas of how to get that done have changed.”

The team and the stadium planners are encouraged to reach out to large advertisers, particularly local enterprises, and come up with different types of seating products, whether they be standard luxury boxes, elaborate “party patios,” stunning field-level clubs for the new Cowboys Stadium’s super-rich, or sections of aptly-named cheap seats like “Big Mac Land” during the height of Mark McGwire’s record-setting with the baseball Cardinals.

While cheap seats are easy to repaint in french-fry yellow, other types of customized seating obviously require more significant design and forethought. If a facility can’t support a healthy variety of events and fan experiences, it becomes another Oakland Coliseum — an albatross of a stadium that nobody loves. (My words here, not Wellner’s.)

Long-term Sustainability

I posed the question to Wellner: what is considered “old” for an NFL stadium? Twenty years? Thirty? Fifty? Naturally, as an experienced designer, his response was both artful and blunt: “It depends.”

“Stadiums that were built in 1985 and later are considered ‘modern,’ and are generally the model for housing NFL football. In the future, as teams’ needs expand I can see preserving a lot of these buildings, expanding them, adding new elements, providing new space, making them contemporary. Many times, there’s no need to tear a building down.”

“If you can save the structure, you can save half the cost of a new building.”

Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City is one prominent example. Built in 1972 and one of the best attended — and loudest — stadiums in the league, it nevertheless had fallen far behind the curve as new facilities sprouted up. $375 million dollars worth of renovation was performed, adding roughly half a million square feet of usable space. This allowed new seating arrangements and luxury suites, upgrading the press box, the addition of several clubs and a “Hall of Honor” to honor the team’s history.

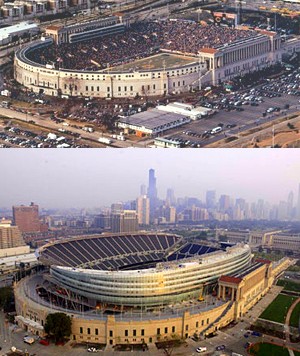

However, retrofitting a modern facility inside a historic stadium isn’t always met with fan appreciation. The renovations to Soldier Field in Chicago (which was not a Populous project) succeeded in modernizing the facility and enhancing the ability to generate revenue, but the resulting mixture of aesthetics has been called “the Mistake by the Lake.”

Every situation is unique. A building that has fallen far behind code or lacks the essential footprint to support modern football may be more expensive to rehabilitate than to replace. Certainly this has been the case with the “convertible” baseball/football stadiums of the sixties, all of which have now fallen to the wrecking ball.

Watch: The demolition of Busch II, our own version of the cookie-cutter convertible ballparks.

Of course, some owners – think Jerry Jones – want to showcase their team in a “top tier” facility regardless of the quality of their current park.

Says Wellner: “I can’t speculate on the fate of the Rams or the Edward Jones Dome. That would require an in-depth assessment of the building, and of what the owner wants to do.” At this point, it’s anyone’s guess.

This article is part two of our interview with Dennis Wellner, senior architect at Populous. Part one introduced the history of NFL stadium design, putting the development of the Edward Jones Dome in context of the NFL’s stadium boom of the 90’s and 00’s.